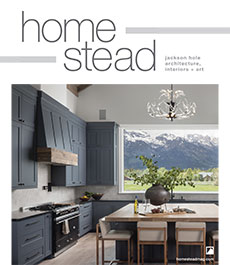

Photos By Latham Jenkins + Ryan Hittner + Peter and Kelley Gibeon

Art can anchor the aesthetics of a room, whether providing a palette upon which to build or adding a moment of whimsy amid an architectural statement. When a piece of art is placed in a prime spot, the space embraces a story—ever unfolding, ever treasured. Herein, four takes on how art animates interiors.

Hop pop

Each piece within this contemporary living space, known as Aspensong, contributes a sense of strong personality, while simultaneously remaining open to possibility. Look closely at the schema set by Jennifer Prugh Visosky of Grace Home Design and see an echoing of outlines, starting with “Bunnies” by Hunt Slonem, reverberating in the Jeff Martin Joinery table, the Studio Van Den Akker slipper chairs, the blocky Sentinel chair and the graceful Holly Hunt Studio floor lamp. Eloquently linear designs, these forms become frames for filling the space with a dynamic lifestyle.

Slonem does this in his art by transforming mundane subject matter into an apparatus for meditation. He begins every day by painting bunnies; their rounded figures serve as his creative calisthenics, the process by which he exercises his creativity. He embraces every association with bunnies, from the White Rabbit in Alice’s Adventures

in Wonderland—and the magical, continual celebration he hosts—to the luck and multiplicity linked to the mammal. Like Andy Warhol—his peer in the New York art scene of the 1980s—Slonem mines the divinity inherent in repetition; the meditative practice of tracing a form ad infinitum.

Born in the Chinese zodiac’s Year of the Rabbit, Slonem sees himself in the bunnies. His daily homage to this subject matter has become an exploration of self within the context of community—just as his “Bunnies” do in Aspensong; they add personality to place, as the homeowner requested. “I just wanted a little whimsy to round the edges of a rather self-important structure,” she says. The bunnies first appeared in wallpaper form inside the elevator. “I told Jen I wanted a surprise when those doors opened—and it does make everyone chuckle. From there, it was a no-brainer adding the ‘Bunnies’ painting.” A harmonious hop from fun to fine art.

Good lookin’

On a meandering road trip from Jackson back to Los Angeles, painter Robert Townsend fell in love with a flickering neon sign in Winnemucca, Nevada. “The Griddle—Good Cookin’” epitomized the mystique of the Old West—alive and well in the New—that Townsend considers his muse. Its script font, rakish geometry and beachy palette—the sign dazzled him so; he knew on the spot he must immortalize it in paint. “Moments like this are the most enjoyable of my life as a painter, because imagining anything is such a magical experience,” he says.

The eye-catching yet unpretentious pop realism Townsend depicts offers “an uplifting snapshot from simpler times,” says Dean Munn of Altamira Fine Art.

Drawn to nostalgic icons (think bubble-gum machines and motor-inn facades), Townsend blends realism with mid-century modernism, all rendered with his skillful hand and gift for color.

Now, his version of “The Griddle”—painted atop a custom 3-D panel—lives as an illusion of the sign itself, installed high up on the wall of a Teton modern kitchen. Channeling the elevation of its original context, its new placement takes advantage of the 20-foot-high ceilings spanning the great-room layout, a jaunty attraction still beckoning people to stop and eat. Mirroring Townsend’s epiphany, the homeowner fell instantly for the painting: “When I first saw ‘The Griddle’ at Altamira, I instantly thought it would be perfect for one of the kitchen walls in our newly purchased mountain modern home. It adds a touch of whimsy to the décor while balancing the other architectural elements of the space.”

Abstract orbit

In theory, “Planets,” a nonconformist painting by Los Angeles-based Bradford Stewart, would seem at odds with the rural vernacular of a log cabin. Not so within the context curated by WRJ Design. Echoing the textural serenity WRJ introduced, the abstract painting complements the subtle layers and natural palette that now define the classic residence. Gracing the river rock chimney, the canvas incorporates the colors coursing through the space, and even transcends the walls to reference the natural world framed by the picture windows: the caramel of the logs themselves, the chocolate brown of the moose bust, the warm grays and creams of the upholstered furnishings, the tender green of spring shoots glimpsed outside, the Tiffany blue of a clear winter’s day. The clanging of his composition seems to reverberate in the studded, steel-and-wood coffee table—custom-designed by WRJ, crafted by Jim Berkenfield—and the charcoal leather arms on the salt-and-pepper linen lounge chairs. His interplay of textures and shapes echoes in the plush surfaces of the real fur pillows, chevron cowhide rug, cashmere throws and Verellen sofa—sheathed in a smoke Holly Hunt mohair. And a Carlo Moretti Murano crystal vase mirrors the intergalactic light he captures in paint. Stewart’s “Planets” sets the vibrant yet harmonious tone of the living room.

As a former composer and musician, Stewart paints with the chaotic beauty of contemporary jazz and classical music. Having studied fine art at the San Francisco Art Institute and California College of Arts and Crafts, he now channels his sense of rhythm and movement into large, abstract canvases. When painting, Stewart imagines an overall feeling—not a final product—and never assumes total control of his materials: acrylics, enamels, resins, polyurethane and pearlescent paints. Embracing an organic process, he layers, washes and mixes materials, ultimately achieving a textured composition rich with motion and voice.

Luminous habitat

After 20 years of musing about butterflies as metaphors—of fragile beauty, of wondrous flight—artist Paul Villinski delved into their biology. With a lepidopterist, he reared native species in the “Butterfly Machine,” an immaculate mobile habitat that reframed their extraordinary delicacy as ecological. “I hope to suggest that the frailty of butterflies, and their utter dependence on appropriate habitat, mirrors our own tenuous condition,” he writes. “There is no separation—we are the butterflies.”

No habitat for his sculpture could be more naturally inspired than Becky Benenate’s West Bank home. Her first encounter with “Arcus” was from afar: Dining at Trio, she glimpsed the chartreuse fan within Tayloe Piggott Gallery. “It made me happy,” she says, an immediate affinity she has since translated into a professional partnership with Villinski; under her art imprint Vivant Books, she is working on a boxed monograph of his work, replete with a micro-installation.

Her editorial mission—to make art accessible to a wide audience—resonates in her cohabitation with her collection. Every piece fills a page while contributing to the complete portrait of a connoisseur: the crystal bowl by George Bucquet she found in Sausalito that now anchors the butterflies’ radiating flight; the pair of Aero Studio chairs on their third upholstery iteration in 25 years. She remodeled the home with her collection in mind, opening up the living space and establishing a neutral palette upon which her colorful pieces could alight—an aerie for art epitomized by the prime placement of “Arcus” above an Art Deco walnut sideboard, facing a Michael McEwan gear chandelier. Light is the current coursing through her collection: the way artists deploy light to transform, as Villinski does through the shadows his butterflies cast; the recollections they conjure—of leaves falling, of past lives, like their own, having begun as crumpled beer cans, collected by homeless New Yorkers whom Villinski hires. More than conceptual meditations, the resurrected insects have become his vocation, and his art has become part of hers. They are the butterflies.